If you happen to be one of Conundrum’s earliest readers, chances are that you have read my summaries of 2011 and 2012 already. I did them mainly because I over-enjoyed retrospective contemplation—not to mention the functionality aspect of it: these posts really help me look at the bigger picture of who I really am, and feel quite significantly more grateful about it.

Now Kundera insisted on the (unbearable) lightness of being—he tried to convince us that when things don’t repeat, they sort of evaporate and float, if not vanish, to the air. It is exactly ‘reoccurrence ‘ that keeps memories heavy enough to stay on the ground. It is repetitions, not mere discussions about them, that sustain history as a reality before humans. Anthropologists however, would probably argue that events don’t gain weigh as they happen again, they simply become a tradition.

Am I trying to give a third shot to a plausibly long-term ritual, or is this only an effort to answer Kundera? I’m not particularly sure. Either way, I’m assuming that you aren’t entirely happy about having another carousel round—which leads me to take the cheesy road for the sake of offering something different this year: 13 words that can help describe my 2013 (mostly taken from Adam Jacot de Boinot’s The Meaning of Tingo). Might get a little sentimental and lengthy on the way, I worriedly hope you don’t mind.

1. Yerdengh-nga (Wagiman, Australia), v. “To clear off without telling anyone where you are going.”

I began the year leaving on a 5-month scholarship to the Island of Lions, and for the first time in my 20 years of life, I understood what ‘missing’ actually meant—in its most naked, honest sense. I remember spending my last day in Bogor crying myself off to sleep as it became clear to me how much I cared about my family and friends, how their presence mattered more than I ever realized (I was emotionally slow—probably still am). I didn’t regret the decision though, I did need to withdraw myself from the status quo—wasn’t sure where I was headed to, but I knew I could use some clear-cut beginning and a fresh start as a complete stranger in a country of introverts.

2. Hiraeth (Welsh), n. “A feeling of sadness, somewhere between homesickness and nostalgia.”

As a consequence, though, I had to deal with hiraeth—a great deal of hiraeth (it was never in my dictionary before). I wasn’t in an exactly perfect shape to make new friends—Mr. Thesis kept on calling my name every time I spent too much time hanging out with them—so I had to settle down with a little loneliness in the libraries. I gave up expecting anything on January 25th, but to my surprise, I had a really good time: a lunch treat by a cool professor, a home-made dinner by Agi, presents from him, Shieron, Iip, and my roommate Chontida—even Kiki and Stefi came over with a real birthday cake! For the first time in my early weeks away from home, I felt content.

3. Tuti’i pas ayina (Persian), n. “A person sitting behind a mirror who teaches a parrot to talk by making it believe that it is its own likeness seen in the mirror which is pronouncing the words.”

One of the bright peeps above might sue me by equating them to parrots (LOL), but this Persian word impeccably represents what Diku, Fahmi, and I (a.k.a. the Evil, Human, and Angel coaches—HAHAHA) had been trying to do with them: to make them see what we saw, that they had the potential to grab the awards we’ve all been waiting for. They say three is the charm, but apparently we had to lose again. Despite completing the hattrick though, I gained many valuable lessons just by accompanying them preparing for and going through the War. So thank you, kids.

4. Lele kawa (Hawaiian), v. “To jump into the sea feet first.”

It will be a complete lie to say that I knew what I was doing when I applied an internship position at the awesome think-tank where I ended up being offered a full-time post at. In Hawaiian, people would say that I lele kawa-ed: I wanted to swim but was still afraid of the depth of the water and all. Regardless, this was my first professional business card (I’m now a research assistant) and needless to say I was quite proud about it without any particular reason. I guess it was a simple satisfaction of finally being hired and making actual impacts on the ground.

5. Ai bu shi shoo (Chinese), adj. “So delighted with something that one can’t keep one’s hands off it.”

Past the lele kawa period, came the ai bu chi shoo phase of working. Today, having worked over 8 months for the institute and experienced many rare opportunities from it (including being involved in the Riau forest fires episode and actually flying to Washington, D.C. to meet all the awesome geeks and researchers there), I should say that randomly applying for the internship was one of the best decisions I made in 2013. This is a pretty new team picture of the Indonesia team taken at the office.

6. Kapusta (Russian), n. “Money (literally, cabbage).”

I hesitated to pick this word because somehow, I was afraid to admit that to a certain extent I am just as materialistic as people I typically hate are. A better word to describe what I’m trying to say is probably ‘afford’ but that’s English, so I had to go with ‘cabbages’ instead :)) Bottomline: I simply have to brag about how good it felt to afford a life of your own, making your own cabbages and spending them as you please (especially if you make four digits per month). I’ve also been blessed with the luxury of making my family a little happier with the small stuff I can provide them with. What I now have to learn about is to keep myself grounded: to truly understand that I do not, in any way, reserve the right to be selfish and annoying just because I grow my own cabbages.

(No, btw I did not buy the sweet-looking Beetle. My friend and I just rented it for our SF-LA trip.)

7. Boghandel (Danish), n. “Bookshop.”

Now one of the good things about having lots and lots of cabbages is that I can buy a loadful of books (insert a huge grin emoticon here). To nobody’s surprise, this year I hit a new record of the number of books I managed to take home. I got almost another one every three days, and barely finish one of them every week. In economics, Rocky would say, this is called over-supply problem. In my language, however, I call this ‘over-blessing’. You are welcome to visit my soon-to-be library!

8. Mokita (Kiriwana, Papua New Guinea), n. “The truth that all know but no one talks about.”

As you might have realized, I finally finished 3.5 years of academic experience in the beloved campus (stole half a year on the Singaporean escapade). Surprisingly though, the day I actually wore my bright-orange toga, I hardly felt anything. I was pretty sure I was happy, somehow, because all the people I loved were actually there: the whole nuclear-family (Eyang, Pap, Mom, Kakak, Dede), the girls (Kiki, Ipeh, Diku), my crazy Booktalk folks (Rocky, Rozin, Johan), most of Batch 2009, etc. But to really try to be conscious about what’s in my head, honestly, it’s mostly empty. The actual satisfaction kicked in after my somewhat successful thesis defense (to attend which Yere delayed an entire class zzz)—graduation day was mostly ceremonial and foggy. It’s almost like a sad entrance—a reminder that you had to leave comfort zone and enter an entirely unknown universe called workplace.

9. Sekaseka (Zambian, Bemba), v. “To laugh without reason.”

Another highlight of 2013 is that I had a great multitude of fun, a spontaneous, unplanned kind of fun. It involved doing a sudden Barbecue cook-out with some of my closest friends, midnight karaoke sessions, and most important of all: an all-around-the-United-States trip (whose tickets weren’t booked until 2 days before we took it)! I guess I simply had enough of being an uptight, downright-organized person, and apparently losing control over yourself is not a bad deal at all. Here’s to more taveling and real friendships in 2014!

10. Tuman (Indonesian), v. “To find something enjoyable and want to have it again.”

You might wonder why (some people actually asked), someone who’d already been doing a lot of youth-related projects and should’ve moved on (read: yours truly), still bother to work on something completely dull and boring like Parlemen Muda Indonesia? Was it a post-power syndrome, or simply the fact that I had nothing better to do? Truth be told (and I’m not trying to cover this up whatsoever), I simply enjoy the entire organizational process: the planning, the crises, the coming to a solution, all the thrill that leading a project brings you—but mostly the planning. Will I do it again this year? Probably not, but not because I don’t enjoy doing it—I simply want to try focusing on something I should’ve been doing this whole time. Something like, you know, actually trying to write a book.

11. Piropo (Spanish), n. “A compliment paid on the street (which ranges from polite to raunchy).”

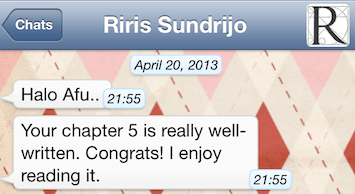

What I learned over 2013: one shall not pretend that he/she is lousy at something just to make people think they’re humble, because clearly humility doesn’t work that way. I believe that’s everyone should find the one thing they truly love and/or are good at, then stand up for it. I also trained myself not only to get used to compliments, but also making the effort to thank these people for their kind words while pushing down the urge to let the rest of the world know about it. (Except for this one, of course. A compliment from Mbak Riris—my awesome dosen pembimbing—even a petty one like this, is simply too overwhelming to be kept a secret. Pardonnez moi. HAHAHA.)

12. Vybafnout (Czech), v. “To surprise someone by saying ‘boo!’.”

And 2013 did that by letting me speak to Vladimir Putin, the very father of Russia. I did not know the possibility of this until I actually stepped onto St. Petersburg and heard the rumors about the opportunity for 20 Delegate Leaders to sit down and have an actual chit-chat with him. I guess the year was just messing up with my expectations and the whatnots. In a generous way. (If you speak Russian, you might also want to watch the video and jump to 1:06:06.)

13. Mahj (Persian), adj. “Looking beautiful after a disease.”

One of the things I decided to confront this year is the insecurity over my not being pretty. When I said ‘pretty’ I did mean the capitalism-imposed version of it: one would quickly conclude that I won’t make it as any magazine’s cover. But this year somehow, just somehow, I had the people kind enough to repeatedly say over my ears that I am beautiful, at least when I was pale and sick :)) What’s actually better: to know that they still stick around despite you being unpretty. I somehow suspect that maybe we don’t really want to be perfect and admired—maybe we just want to be ugly and accepted.

***

Anyway. There are some words that I thought would mark 2013 but proven to be completely wrong: ‘torschlusspanik’, a German word for “the fear of diminishing opportunities as one gets older” and ‘parebos’, an Ancient Greek meaning “being past one’s prime” are two of them. But no, being 21 years old proved itself to be one of the best times of my life.

Andika told me that life is supposed to be full of surprises and that’s what you need to be prepared of. To have more of them. Some people try doing ‘yetu’, a Tulu-Indian word for “gambling in which a coin is tossed and a bet laid as to which side it will fall on“, but the wiser ones know that it’s a futile effort. You just have to take the roller-coaster ride and feel the breeze in your hair.

Now comes the part where I share what I really wish for 2014: to stay grounded and unpretentious. Basically to still find comfort in riding angkots-quo-Commuter Lines, as well as eating street foods (I’m sure Angkringan will forever be good). I won’t promise myself to write more, but I hope my upcoming 2014 journey would be meaningful enough to take notes about.

Oh and here goes a little quote that is totally unrelated but so beautiful I simply cannot resist to not use it to close this long post:

“Great conversations are like beautiful squares in foreign cities one finds at night and then doesn’t know how to get back to in daytime.” —Alain de Botton