I miss my friends.

Although saying “I miss my friends” would be such a gross oversimplification—the truth is: (1) I don’t even know whether I’m a ‘friend’ to someone these days (it does get confusing), (2) it’s not so much about not being able to spend time together that it is about not being in the physical space that allows us to spend such time in the specific ways we used to (it will make sense below), and (3) life has led you to see the world (or yourself, or each other) differently and you simply can’t go back to ignorance.

I. How do we define a ‘friend’, again?

In between all the growing up and heartbreaks in your 20s, the border of ‘friendship land’ had gradually became more political. I often find myself asking whether I am still someone’s friend: Is it enough that we hang out from time to time (bilaterally and as a group), or do they need to call me when they struggle? What does it mean if you can’t tell if they’re genuinely happy for your achievements? Do they still consider you a friend if they keep prioritizing their demanding job, spouse, or baby?

Some (typically from school or work), pushed through and made it to your 30s: those who stepped in during your hard times, embraced the inconveniences of maintaining regular checkins, transcended through the traps of envy and celebrated your highs.

Making new friends, however, is a whole other ball game. Today, it’s too intense to call those you know through professional connections more than ‘colleagues’, those you meet in the studios (dance, pilates, or otherwise) were now ‘acquaintances’, and men decided to either be interested in you romantically or not a all. People simply don’t wear their heart on their sleeve anymore and ask to become someone’s friend.

Unreciprocated friendship proposals are just as real as romantic ones, by the way: those awkward invitation to “have caffeinated beverage”, met with delayed ‘reschedules’ (although sometimes they really do need to take a raincheck—too busy, too depressed, or simply are clear about their priorities—good for them, really.)

II. The unbearable lightness of growing up (and apart)

Even two years after resigning from my corporate job, I still hang out regularly with my ‘friends from the office’. They are some of my most favorite human beings on earth, and we’d make up excuses to dine together or have a roadtrip out of town. What I miss, however, is much simpler: those times that they would stop by one another’s office and just chat randomly until at some point one of us burst laughing on the floor, or walked to grab coffee together.

You know, the kind of ‘friendship’ that effortlessly fills your day, not the one you have to carve out time for.

It’s even less complicated making friends at school: you have to physically be in the same classroom or bump into each other in the canteen after all, tackle assignments together on those roundtables—every day the university will give you hundreds of reasons to make a friend. And in those random walks, your souls find one another, sparks happened, and the rest is history.

I’ve lost one too many friends to their dreams. Don’t get me wrong, I am elated for them: those pursuing academic degrees, better jobs—no, better lives abroad. At every farewell, we will promise one another to ‘stay in touch’ but who are we kidding: we lost touch. I cherish the annual calls we’d have, and all the big news (a wedding, a newborn, a new house) about them, but it’s simply not the same.

Oh what I would kill to be having those collective walk during lunch breaks again.

II. Most importantly: you have changed

On top of the list of beautifully tragic bases for missing (losing) a friend, is when you have radical clarity on what matters in life, and they simply don’t fit in that picture anymore.

As you get older, the universe will nudge you to get closer to your fully aligned self—it will put you in situations where your values are tested in the deepest sense, and sometimes it inevitably means breaking up even with some of your closest, most treasured friends.

This I think is the unique possibility unlocked in our 30s: the only time we actually could afford to be alone, is the time we are clearer about what we want, and what we find important. We have enough time to catch up and become better emotional regulators, we don’t have to please people anymore. Voilá, now you have clearer boundaries and therefore fewer friends.

***

In case not obvious: Attachment styles, as I discovered this year, applies to all kinds of relationships: your patterns of anxious, avoidant, or secure selves will show up in how you maintain your friendships, too. As someone with a ‘disorganized attachment’ tendencies, I am not the easiest to be friends with. I also tend to conclude/judge, prescribe solutions too quickly, and hyper-rationalize—yet in all my imperfections, I am grateful for the fact that a few people still find a friend in me, including those I haven’t even met in person for quite a while now: I love you guys.

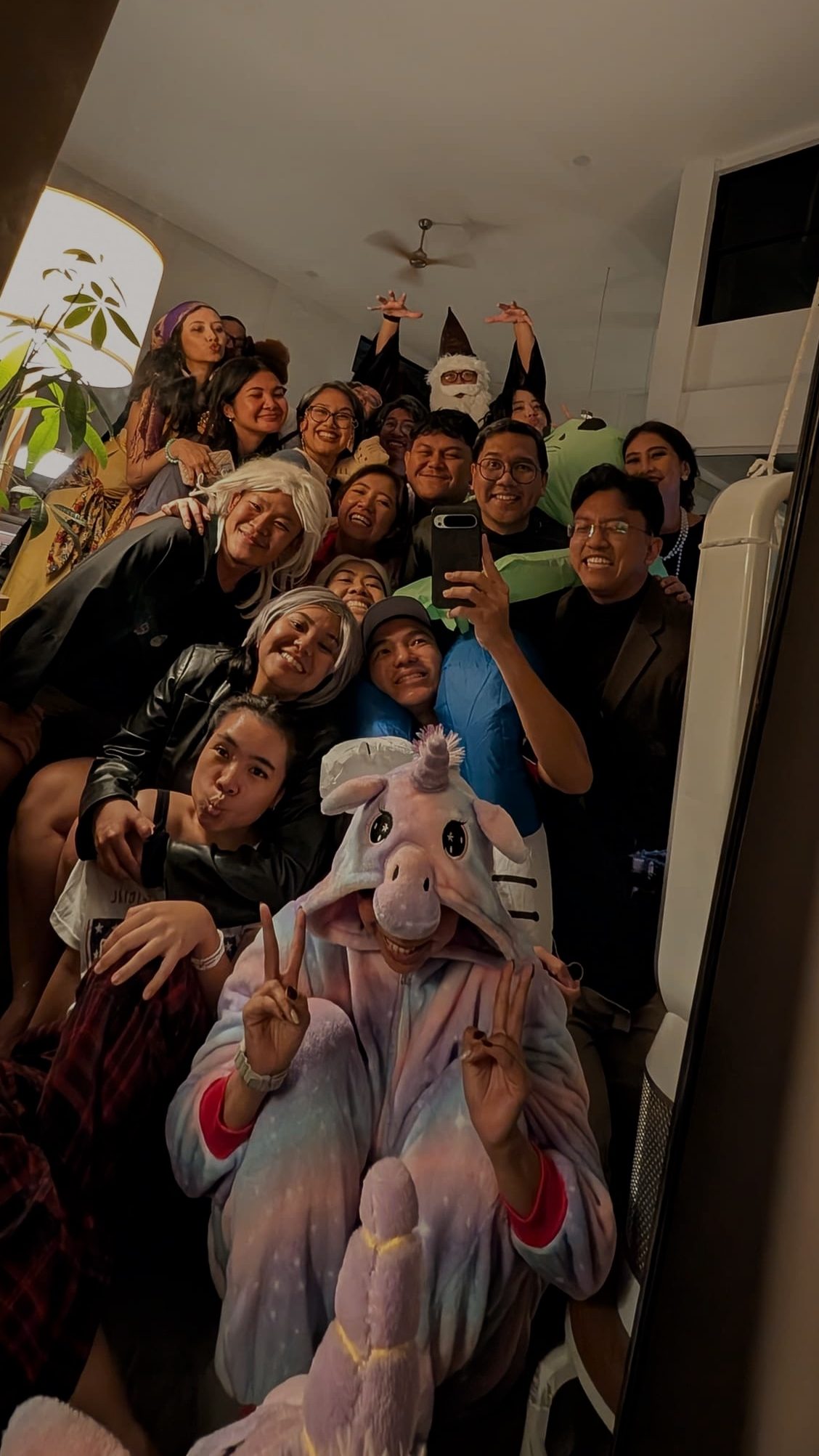

So have that video call, that coffee catch up, that get together.

Life’s too short not to enjoy love in any form we could ;)